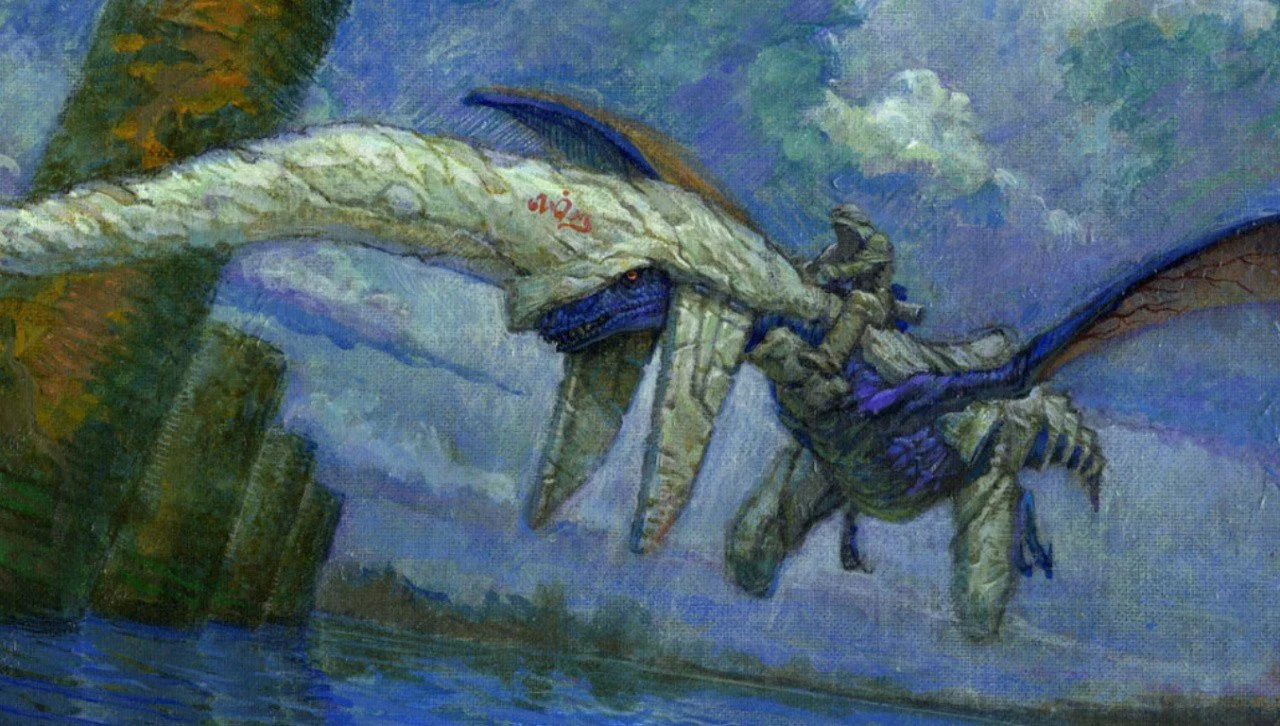

the wings of a blue dragon

I remember Panzer Dragoon.

On some of the darkest nights of frozen New England winter, my brother and I would sit silently as the balding tires of our family’s Ford F150 slipped along the salted roads. My parents mostly disliked each other, and they sat silent too. We were one of those families that didn’t talk, and my brother and I were children who didn’t ask questions. But we felt a lot.

Later we’d stand in the dry, overheated air of Sears. My mother would walk off, leaving us kids to hover like jellyfish around a father unnecessarily browsing racks of bandsaw blades dappled with rust in their heat-formed plastic coffins. We’d wait for a moment to ask if we could go somewhere, anywhere else.

Eventually it happened. One of us would build the courage to break the silence, and then we were away, kids running amongst the chromium racks of unbought clothing, streaking past the shelves of synthetic leather shoes and underwear and plastic appliances, all destined for the landfill, pointless in the ghost store, itself pointless in a dying mall in a nowhere town.

We ran and the soft slaps of the thin soles of our weathered tennis shoes made thin applause, until we glimpsed the simple paper sign dangling at the end of two thin strings clamped into the drop ceiling: “Electronics.” Like a checkered flag, it spurred us, and here we found our great relief. A small counter tucked into a quiet corner of the store where towers of wire shelves held video games, and amongst these stood a great obelisk, a totem of reverence, a demo kiosk.

It was 1995. The Sega Saturn was just a few months old. A dramatic and expensive thing which my brother and I could only dream of owning, Sega’s most powerful game system sat humming under a plastic bubble shell beneath an elevated television angled perfectly for our young eyes. For the last few months of our weekly visits, it had played a tantalizing loop- the attract demo of Sega’s most ambitious title, Panzer Dragoon.

My brother and I had never seen anything like it. A three-dimensional polygonal dragon soared through endless exotic lands with a rider as small as me perched between its wings. It defied gravity and reality. It carried the weight of the world, and the hopes of all people. Miraculously, if I reached up just a bit to the hovering controller, it could carry me too.

We were spellbound by the dance of wings and light. Every frame of limitless flight atop the shoulders of an armored dragon promised a reimagined life, one in which we could move with agency, destroy or escape that which hurt us. A soaring orchestral score rang through the quiet space. Photons beamed from the CRT and danced against our retinas. Our brains and bodies were literally filled with the light and sound of fantastic places, and hope, and for a few moments once a week, my brother and I did not know the nearness of our unhappiness.

But all things end. The demo would allow us to play for just fifteen minutes, after which the system would die as suddenly as if the power cable had been ripped from the wall. And it happened, as always, in a startling flash of light, after which the screen would go black, and for the briefest of moments we would see ourselves reflected, distorted and small in the convex shadows of the empty screen. We’d see the cavernous emptiness of the ghost store, and the worn linoleum tiles, and the hollow pinholes of the drop ceiling and the racks and racks of pointless shit expensive and expansive, stretching into the shadows. Our smiles would fade and we’d avoid the gaze of our shadowed selves until the Sega Saturn once more fired to electric life.

Then we could once again fly, and we did, until called away. And we’d again go silent and tread lightly. On eggshells. Waiting for it all to cycle again.

I didn’t understand my desperation then. In single digits, you’re too involved in living your small life to really know anything about it. Your reality feels like the only possible reality. Only now, looking back from the vantage point of my fifth decade of life and with two small children of my own, have I begun to understand just how bad our childhoods were.

One year after my first flight atop a winged savior, my family would be broken. My mother gone, my brother missing, my father ordered by a well-meaning court to have no contact with his kids, and me, left to live alone amidst echoes and ghosts, in the stale basement of an elderly unmarried relative who may as well have been a stranger. During these months of isolation, there were spans of days where I’d not hear another human voice. It was then that a deep well was dug in me from which a sadness springs even today. This sadness burbles up from somewhere endlessly and saturates my life. It fills me sometimes, and threatens to capsize me. It demands continuous bailing.

Today, my life is good. It has been highly functional, and there’s a lot for me to love and to be happy about. But I know that I will never be happy the way that some others are happy.

That’s okay.

Tomorrow will be a new weekend. I’ll get up and make my wife a coffee in the morning and deliver it with love. I’ll wake my two daughters with gentle care and make them breakfast. Later, needing groceries maybe, I’ll ask if they’d like to come, and if they do, we’ll go to the big store which happens to have a video game section.

There they’ll find the bright red kiosk and the hovering Nintendo Switch, and their little feet will carry them to it, and they’ll grip the controllers and laugh and play and find happiness as the photons dance against their retinas and the music of adventure vibrates their bones. And when the demo ends, their smiles and laughter will continue, because their childhood will be one of happiness. Their joy will not demand a winged escape or a dragon to carry them. I’ll watch them play, and smile to know that for as long as we’re able, my wife and I will lift them, carry them.

We’ll help them to fly, and that will be enough.

Interview Transcript: Sayonara Wild Hearts’ Simon Flesser, March 2025

For Retro Gamer Number 276, I interviewed Sayonara Wild Hearts' director Simon Flesser. We talked about Simogo's musical arcade mashup, and why it's destined to be a future classic.

For Retro Gamer Magazine (#276), I interviewed Sayonara Wild Hearts' director Simon Flesser. We talked about Simogo's musical arcade mashup, and why it's destined to be a future classic.

Here’s the mostly unedited transcript of that conversation.

James Tocchio: Can you describe the first spark of an idea that eventually lead to Sayonara Wild Hearts?

Simon Flesser: Listening to the Lord Huron song “World Ender,” I had a vision of a game of a masked avenger on a motorcycle. At the same time I had started drawing characters inspired by the teddy girl culture, wearing masks. These were the two first real sparks that ignited the idea.

James Tocchio: Prior to Sayonara Wild Hearts, Simogo’s best-known projects had been puzzle games, and your latest was another excellent puzzle game called Lorelei and the Laser Eyes. Do genre labels matter to you, or do you see your creative identity as fluid and transcending traditional categories?

Simon Flesser: I guess genres are useful for trying to explain a game to a potential audience, but we don’t really make strict genre games, and don’t have an interest in specific genres in a traditional sense. Perhaps more on the contrary, we’re interested in exploring things that we think we can push in other directions than they usually do. That could be things like trying to have more moment-to-moment gameplay in text based games, or puzzle games, or trying to find ways to simplify action games while not compromising on the sensation of spectacle, like Sayonara Wild Hearts.

James Tocchio: I’m a Sega fan, and when playing Sayonara, I was constantly feeling the influence of some of my favorite games, including OutRun, Super Hang-On, Rez, even Panzer Dragoon and Space Harrier. Can you confirm that you’re Sega freaks like me? Could you elaborate on how these influences shaped the gameplay and whether there are additional inspirations that played a key role in its development?

Simon Flesser: We grew up with mainly Nintendo and Amiga, but it’s definitely a correct observation that SWH has some very strong SEGA influences. In later years I’ve come to really love specifically OutRun 2, but like everyone else I also like Rez.

James Tocchio: What’s the most interesting video game you’ve played in the last year, and what elements of that game resonated with you?

Simon Flesser: I’m not too keen on new games, but in the last year it would have to be Animal Well, and Emio - The Smiling Man: Famicom Detective Club. The first one for its great sense of mystery and the second for its humanity and surprising themes for a Nintendo game.

James Tocchio: Beyond video games, are there specific films, musical genres, or visual arts that have recently inspired your design choices?

Simon Flesser: Video games as a culture overall, anime, the Teddy Girls subculture and the cafe racer subculture [were influential when making Sayonara].

James Tocchio: The cafe racer influence is right at the forefront, and as a motorcycle builder and rider myself, I can tell you that the game does well to provide the feeling of racing a motorcycle. Are you motorcyclists?

Simon Flesser: I personally don’t like motor vehicles in real life, as I’m kind of nervous about traffic overall, but I love the sensation of speed, especially in games. I don’t even drive a car, but Gordon [the game’s co-creator] drives and owns a motorcycle.

James Tocchio: Sayonara Wild Hearts tells its story with deliberate minimalism, leaving much open to interpretation. How do you approach storytelling, and what do you hope players discover in its ambiguity?

Simon Flesser: To me, SWH is a broad allegory about new beginnings and dealing with the past and the future. I think players should interpret it however they see fit. It was never meant to be about about something specific or concrete, for that reason. I think the entire idea with an ambiguous story is that it is open for interpretation and so I don’t want to force my exact ideas about what the story means.

James Tocchio: I love games which feature a simple core concept, refined and perfected, however many of today’s most popular games feature hours long on-boarding just to teach us how to play the game. I struggle to enjoy this, especially as I get older.

Sayonara Wild Hearts launches into its gameplay after a brief cinematic. There is no onboarding or tutorial. We’re simply dropped into a magical rollercoaster of light and sound and intuitively know what to do, which I consider the result of intelligent game design. Your latest game, Lorelei, is more complex, but relatively speaking it is similarly refined.

What are your thoughts (broadly or specifically) on game design related to complexity vs simplicity? How do you approach the balance between simplicity and complexity in game design, especially when considering player onboarding and intuitive play?

Simon Flesser: Both Lorelei and the Laser Eyes and Sayonara Wild Hearts were designed with only one input, so that they could be picked up by people who have never touched a game before. Both were designed to be complex in different ways.

Generally I think the best way for teaching the player is to just have them learning by doing, in non-threatening circumstances.

James Tocchio: Where does the tarot card influence in Sayonara Wild Hearts come from, and what does it symbolize within the game?

Simon Flesser: I grew up with witches so I have always had tarots around me and find them fascinating. They’re meaningful for themes, but also come with a lot of free visual ideas.

James Tocchio: The development of Sayonara Wild Hearts took four or five years and involved a larger team of creatives than previous Simogo projects. Could you discuss how you and your team managed creative differences to produce a unified artistic vision?

Simon Flesser: I guess you need a strong vision, and that takes a while to take shape. So it was a lot of iteration until we understood what Sayonara Wild Hearts was and what would fit and not. As more ideas come together, it gets easier and easier to understand what fits and what the game needs. We cut a lot of content to get there.

James Tocchio: What are Simogo’s favorite snacks?

Simon Flesser: As we get older we have to be mindful about snacks! We’re all big enjoyers of coffee, but I don’t think there’s a unified opinion about snacks. In fact, I don’t think we snack that much.

James Tocchio: SWH is a pop album, a game, a piece of digital art, and it must have been difficult to combine all its elements into one cohesive experience. Can you share a specific moment during development when art, music, and programming converged into a breakthrough moment?

Simon Flesser: I [originally] had an idea about a much grittier and pulpier game, but when playing a rough prototype of driving with The Fool in the night as playlist of pop music with things like Robyn, CHVRCHES and Carly Rae Jepsen came in, the entire idea about the game shifted from one day to another. The very same day I contacted Jonathan and asked if he could do a test to write an energetic pop song.

James Tocchio: Did you experiment with any unconventional gameplay mechanics that ultimately didn’t make the final cut?

Simon Flesser: There were a ton of things we cut from the game, often because we deemed them too complex or that they slowed the game down. We had story bits in third person in which you’d walk around, between songs. At that time we imagined the game only being the main lyric pop songs, but instead opted for many small levels that could explore smaller ideas instead. In this concept the Fool would get sucked into different medias, and ‘Begin Again’ took place inside a movie, while ‘Mine’ took place in storybook castle.

We had ideas about The Fool learning and using a new skill for each main song. One of these was splitting herself in two, and you’d control two Fools on the stage, sometimes on splitting tracks. We had an almost finished level with this, which was fight against The Stereo Lovers in a castle. Some of these concepts would survive in different shapes and you can see parts that are inspired by this in final Stereo Lovers levels.

James Tocchio: I have read that the development of SWH was quite challenging and stressful. What were some of the most significant challenges you encountered during the four or five years of developing Sayonara Wild Hearts, and how did those experiences shape the final product?

Simon Flesser: While we did create a lot of systems, we didn’t create enough tools to interact with them, so work often became laborious and slow, which led to frustration and stress. We wanted to make a game that constantly shifted and that felt custom all the time, so for a lot of the time it wasn’t even possible to systemize things within the game.

Each stage is built like and was supposed to feel like one long custom animation that always syncs to the beat, and that idea in itself was perhaps too much for a small team like us to handle.

James Tocchio: Game development can be intense and demanding. What strategies do you employ to maintain creative momentum and avoid burnout during long development cycles?

Simon Flesser: Finding ways to keep the development joyful every day. The best way for this is to design games and tools that allows for a lot of progress constantly, even in a big project. It’s also important to highlight progress to everyone on the team, so that everyone sees and understands that we are always moving forwards together. In that respect, Lorelei and the Laser Eyes was a much better project for us.

James Tocchio: The identity of SWH is inextricably linked to its soundtrack, which is a sort of energetic electro-pop album bursting with emotion.

Jonathan Eng’s early tracks leaned towards an electric guitar, California surfer, garage rock vibe. What drove the shift towards the electro-pop sound that defines the final version of Sayonara Wild Hearts?

Simon Flesser: I mentioned a defining moment before, but part of this was also to give the game a more feminine image and feeling, which would make the game unique from games which are often very masculine and macho.

James Tocchio: Could you share how the process of creating and integrating the soundtrack was interwoven with game programming and design decisions?

Simon Flesser: Typically, we’d have a sketch for song, or a more or less finished song, that I’d write a scenario for, and then making more and more edits along the way.

James Tocchio: Did the soundtrack come first, influencing the gameplay mechanics, or was it an iterative process where music and gameplay evolved together?

Simon Flesser: It was very much a back and forth between me and Daniel Olsén. Sometimes I’d have an idea for a level, and I’d come with a request to Daniel like ‘This one needs the snare and base drum to be specifically clear and be closer to a hip hop song in tempo, as we are shifting dimensions on the beats.’ Other times, we would have more finished songs, and I’d have impossible requests like for ‘Inside’ where we had to make the ending longer so we could fit the entire last bit with the Death monster. The most impossible request was the last level medley, and it’s still hard to believe how Daniel was able to weave together all those songs in the way he did, while constantly changing to fit requests about lenght and intensity.

James Tocchio: Could you elaborate on the challenges of designing gameplay that is so tightly integrated with the music, for instance, the rewind mechanic during fail states?

Simon Flesser: Basically the entire game is built like an animation, and when designing them we can scrub the entire timeline, frame by frame. It was a big challenge to make, and not how you traditionally think about games. But it was needed, as everything needed to sync up perfectly to the music.

We did for a long time have mechanics that were tied to this, which involved slowing down time, something very reminiscent of bullet time mechanics seen in other games and movies. We’d have one dreamy time stretch version of each song, and when you held down the button you’d consume a meter that made the level slower, but the character would still control as fast.

James Tocchio: What are your favorite game soundtracks?

Simon Flesser: Both me and Daniel love the WarioWare soundtracks and often call tracks ‘Dr. Crygor-like’ if it has a specific vibe.

I generally like most songs from Hip Tanaka. I love the soundtrack to Space Invaders Infinity Gene. I also quite like Silent Hill 2’s soundtrack. But I think Yoshi’s Island is my all time favorite.

James Tocchio: What does ‘success’ look like for you, not just commercially, but artistically?

Simon Flesser: If a game realizes its idea, and does what it sets out to do, it is a success.

James Tocchio: Do you think you’ll create a follow-up to Sayonara Wild Hearts?

Simon Flesser: No. But it was fun to revisit and finalise Remix Arcade with the new PS5 version.

James Tocchio: Can you share any hints about future projects from Simogo?

Simon Flesser: In the nearest future it’s about looking to the past before we move along to the future.

Interview Transcript: Richard Jacques, August 2025

Richard Jacques has created scores and music for some of the most recognizable properties in entertainment, including James Bond, Marvel, and Sonic the Hedgehog. I’ve interviewed him twice. Here is the full transcript of my conversation with Richard Jacques (focusing on Metropolis Street Racer).

In 2022, I launched a Dreamcast-focused website and Youtube channel. This silly passion project ended up opening some interesting doors, including the opportunity to work as localization editor on a particularly neat game translation project, and the chance to appear in the pages of Retro Gamer Magazine.

This latter event came about because the December 2023 issue of (Retro Gamer #254) was to feature a cover story written by Nick Thorpe focused on Sega’s final home console. Being familiar with my Dreamcast content, Nick reached out to me as a source.

I guess he liked my writing well enough that at the end of our conversation, he suggested I pitch to the magazine, which I did.

A few weeks later, I spoke with Richard Jacques, the well-known composer of such game soundtracks as Sonic R, Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy, and Mass Effect. We had a great conversation, and the content of that interview became an “In the Chair” feature article in the March 2024 issue of Retro Gamer (#257).

A while later, and with about ten issues of RG under my freelance belt, I was asked to write an article for the magazine’s recurring “Music Memories” feature. In this feature, the magazine spotlights a game with a phenomenal soundtrack, often with interview content from the composer or musician who created it. I chose Metropolis Street Racer, Bizarre Creations’ groundbreaking Sega Dreamcast racing game, and I once again spoke with Richard Jacques, who composed the game’s music and created the game’s sound effects.

That article appears in the September 2025 issue of Retro Gamer (#277). As is always the case, the interview included much which could not fit in the magazine. Here’s the mostly unedited transcript of my conversation with Richard.

James Tocchio: Please introduce yourself and give us a very brief list of some of the things that you've worked on.

Richard Jacques: My name is Richard Jacques. I've been composing in the video game industry for just over 30 years, started as an in-house composer with Sega back in the nineties here in London. I worked on Sonic, Jet Set Radio, Marvel's Guardians of the Galaxy, Mass Effect, James Bond, Littlebigplanet 2, Overwatch, 2. A whole bunch of stuff.

James Tocchio: We're here today to talk about Metropolis Street Racer, the Bizarre Creations Dreamcast racing game that came out late in the Dreamcast lifecycle. It’s widely regarded as one of the best racing games on the system and one of the more inventive racing games ever made. It was interesting for many reasons, including its “Kudos System,” which was based on how stylishly you drove, and because the races didn't take place on racetracks but rather on real world roads of three major cities (London, Tokyo, and San Francisco).

So there were a lot of really new and interesting ideas in this racing game, and one that you were instrumental in was that each city had its own soundtrack. These were played through radio stations and every city had its own flavor. It would be jazz. It would be rock. It would be hip hop, or dance, or club, or EDM.

Richard Jacques: You’ve got it.

James Tocchio: Can you talk with us a little bit about the genesis of all this, what was the creative process like?

Richard Jacques: We’re going back to around 1998, or maybe early ‘99. This was when I was still in house at Sega Europe, in London, and I had a meeting with a producer about, you know, what work I've got coming up, and they said that they had just signed this new game with Bizarre Creations.

So we went up to Liverpool to Bizarre Creations office, and I had a meeting with all the leads there, the game designer, the lead coder, all the management team, and because I was still in house, I was sort of the central audio resource, if you like, [making] everything, music, sound, dialogue. I was literally the only person, pretty much, certainly within the UK office, so I was supporting any games that were made internally and with Sega Europe's third party. MSR was kind of a first party title. So, it was an exclusive title being made exclusively for Sega Europe for the Dreamcast. So when I knew I was going to be working on it, I knew that I would have to do all of the music, all of the sound design, including all the car sounds, all the dialogue. Basically anything you hear in that game, with the exception of the real life radio advertisements, I created, including writing DJ scripts and all that kind of stuff.

James Tocchio: It must have been an immense amount of work.

Richard Jacques: Huge amount of work, because the soundtrack is quite big anyway. I mean going back to the concept, it was my idea to put a radio station system. I will give thanks and due credit to GTA 2, I think, which I was playing in my spare time at the time, the top down version. Was a fantastically fun game, and they had a great radio station system there. So I think I was certainly paying homage to them, but we wanted to do something a little bit different, because we wanted it to be sort of more realistic, since we had photorealistic cities. And the reason those three cities were chosen was that's where Sega's main offices were. In the US they've relocated to LA, but all the head offices for Sega at the time were in those three locations.

Richard Jacques: So we had these amazing photorealistic looking tracks and real world licensed cars. So the emphasis was kind of more on the realism, and I thought, I don't particularly like as a gamer being forced to have one particular style of music, unless it's something like Wipe Out, which is heavily stylistic. If someone gives me a bunch of rock tracks to race around an oval track, it's not really going to do a lot for me as a gamer. So I wanted take it a bit further if I could. And basically, when I wrote the concept down, I was looking at the sort of popular styles of music in those three territories, and the kind of radio stations that would play them. Obviously London, where I'm from, I'm familiar with all of them, and they were based on three real life radio stations. So Kiss FM plays all the dance music, Jazz FM plays all the jazz, Capital Radio is kind of mixture of pop and that kind of stuff.

And I sort of found similar radio stations after researching and speaking to some friends in the other territories of San Francisco and Tokyo. In Tokyo I knew the music scene well from having gone over to Sega, Japan, many times working on different projects, and the same with San Francisco for going to their offices and conferences. So I wanted to get a flavor, and I did talk to some of the localization producers in those territories saying, you know, what's current? What are the current trends? Things like that? I remember going to Japan and just going to a record store in Akihaba and just filling my bag full of CDs and vinyls, listening to the J Pop and all kinds of things.

You know, this radio station is going to be jazz. This one's going to be R&B. This is going to be a mixture. This is going to be EDM. And then I identified three or four different sub genres, or real life artists, but they're not particularly supposed to be a pastiche of those artists. They're supposed to be a sort of homage to the styles to get them into the cities and make them feel realistic.

And then I also spoke with the marketing team at Sega Europe, about two specific issues I really wanted; one was to give the player freedom to compile their own in-car CDs. So when you're not listening to the radio, you could make your own playlists, and playlists weren't a thing back in 1998. There was no Spotify or anything like that, but I wanted to make sure the player had the choice to choose their favorite tracks, that they could then save on their VMU, which is the memory card for the Dreamcast, and play whatever songs whenever they wanted. So hopefully, it was giving the player choice, and they could create their favorite playlist.

And I also wanted to have real life radio ads, because, to my knowledge, it had never been done at that time, and I've never heard it since. I'm sure other people must have done it, but I figured that'd be really cool hearing stuff you would hear on the radio with all these quirky voiceovers. And It just added to the the realism of feeling like you're in in those particular cities. So all the advertisements, I think, were all real life ads. And then I had to write the DJ scripts.

Richard Jacques: So I came up with some concepts for who the DJs would be, what their kind of age group would be, who the radio station’s aimed at. Listener demographics, weather, traffic reports I had to write as well. So yes, everything.

James Tocchio: Speaking of the DJs. I know there was a man called Darren Johnson, and I think, Chris Turner, and I'm curious if these were real people or perhaps Easter eggs of friends names?

Richard Jacques: There are some friends names in there. I don't know about the DJs in particular. Chris Turner is one of my university lecturers Darren Johnson is completely made up because it was just kind of a slightly more useful sounding name. The Dj names are mostly fake.

But now you've got me thinking there may be one or two shout outs to some friends of mine in the DJ scripts. When one of them saying, “Oh, this is for so and so, or giving a shout out, blah, blah!” Yeah there's some friends of mine in there.

James Tocchio: How many songs did you compose?

Richard Jacques: 27 in game, and then some menu and credits and things like that.

James Tocchio: What can you tell us about the process of recording the car audio, engine and exhaust sounds?

Richard Jacques: The car engine sounds had to be realistic. So we had to record all the car sounds. I spoke to some friends about how and where to do that. Although I had done quite a lot of sound design at SEGA Europe, I hadn't done real car engine recordings before. Yeah, I'm trying to remember. I know we recorded a lot, and I forget how many were in the actual game. If memory serves correctly, I think we recorded about 30 cars.

Now, there may have been variations to the size of the engine, the type of engine. So some of them had a rotary engine, which is a completely different sound, turbos, which have completely different sounds. Some of the exhausts are very different. I think we did about 30. We spent about two weeks at a motor industry facility in the UK, which have what's known as a semi-anechoic chamber, which is where they do all the emissions testing. So when they have a new vehicle to put on the market, they do the noise testing in this chamber.

Recording a Fiat for MSR. In the driver’s seat, Sega Europe producer Kats Sato.

Richard Jacques: It has a rolling road, so you can put the vehicle under load and up to a certain amount of revs, and it's sort of soundproofed so it gives a really clean recording. I took a bunch of microphones and equipment from the Sega studio in London, and we drove down with the assistant producer and the main producer in Sega, Europe. And we spent ages recording all the different car sounds in different rev ranges under load. We had binaural head inside the car. We had, I think, eight microphones around the car, a couple on exhaust. We recorded again with the hood up, various positions, and we did some stuff on the high-speed circuit as well. Some of it was usable, but most of the stuff we got from the chamber where we did the main recordings.

James Tocchio: Are you a car enthusiast?

Richard Jacques: Not in the slightest. No. I love racing games, that's for sure. Always have done and still do now. But I'm more a boat person than cars.

James Tocchio: I was going to ask if you have a favorite car.

Richard Jacques: Well, it would have to be probably going back to my gaming days, probably the Toyota from Sega Rally, the Toyota. Was it the Corolla? I forget now. Or the Ferrari from OutRun, you know.

James Tocchio: The Testarossa.

Richard Jacques: Exactly.

James Tocchio: And you worked on OutRun 2, so that’s lucky. But let’s not get sidetracked. Prior to this interview I was looking at the cover art for MSR, the Opel Speedster. I remember when this game came out, I think I was 16 years old, something like that, which in the USA is the time when you get your license. And I was a huge car nerd and I remember seeing this cover and thinking “That is the best car I've ever seen.” And tragically for me, we never got it over in the United States.

Richard Jacques: Oh, did you not?

James Tocchio: They never sold it here.

Richard Jacques: I mean, I used to see a few. It was quite a coup for Sega to get that for the front cover and have it in the game, because it was so brand new, and a very different kind of car. I'd never seen anything like that before. It looks great on the cover.

Richard Jacques: I always wondered who was in the driving seat, because I'm sure it’s one of the producers from Sega Europe. Okay, I'm looking at it now. So yeah, the person driving, I'm not sure. But if you look in the background. There's a silver I think it was a Fiat. I think that is the producer's car, because I remember the registration.

James Tocchio: Oh, that's funny!

Richard Jacques: Yeah. So the producer in London, Kats Sato is his name. I think he's working at Sumo now. Really great guy, and I'm pretty sure that is the car. He had the silver one.

James Tocchio: There's a funny story I’ve read about Kats Sato, maybe you’ve not heard this one. Are you familiar with the story about how he discovered who was developing the Formula 1 games for Sony? They were at a conference, and the game was running, and he wanted to know who was developing it for Sony, so he pulled the power cord for the demo so that when they plugged it back in and it booted up he could have a chance at seeing the name of the company that was working on it. And he found out it was Bizarre Creations, which led to SEGA securing MSR for the Dreamcast.

Richard Jacques: [Laughing] That wouldn't surprise me. Knowing him as I do. He's got an amazing sense of humor, and great businessman and a great producer. I can’t comment on that story either way, but it would certainly sound true of the person I know.

James Tocchio: This may be touchy, but tell us about your mishaps in the car recording chamber.

Richard Jacques: Well, I'll keep it very loose, if I may. There was one. There was a couple of days during recording where I was off sick, and I couldn't make it. Just had some flu bug or something, and I couldn't make it to the recording. And the assistant producer had seen what I was doing, and he was operating the recording stuff, and I had no qualms [about him running things in my absence]. I looked at the list and said, “Oh, we've got these three cars tomorrow, and these three cars on Thursday or whatever. And yeah, don't worry. You'll be fine.”

Richard Jacques: But not really being a car person, as I've mentioned, I didn't realize that one of them had an automatic gearbox, and the only thing I'll say is that when we finished recording, we pushed it a few miles down the road, and it no longer had an automatic gearbox. That's all I will say.

James Tocchio: Can you say which car?

Richard Jacques: I think it was a Mercedes SLK.

James Tocchio: Oh, that’s a cheap one. No big deal.

Richard Jacques: Exactly. Yeah.

James Tocchio: So getting back to the music. You compose 27 songs, plus some menu music. Do you have a favorite song or radio station.

Richard Jacques: Well, that's a good question. I guess in terms of capturing that sort of moment in time, because all the different songs are very loosely based around artists and bands that would have been around at that time. I'd say, one of the London ones, maybe the dance station in London, London Underground FM. I like all the jazz stuff, but that's sort of strewn around between London and some of the radio stations in Tokyo, as well.

James Tocchio: Yeah, the jazz tracks are really impressive. I remember you telling me that when you first got the job at SEGA, they were very impressed with your versatility, and the range of music that you could put together.

Richard Jacques: Yeah, this one was almost the ultimate test, really, because in terms of popular music there's not a lot that wasn't included. So it was a test, and, you know, being as self-critical as I am, I think some songs work better than others, but I think, overall, they all had a certain quality and a certain feel that worked with the game. And yeah, I was happy with the results to be honest. But it was, you know, chopping and changing from dance one minute, rock the next, and then next week we're doing country. And then, the week after we're doing something completely different.

Richard Jacques: Certainly, you had to be on your toes, and I wanted to make sure it was authentic, and the production was up there. So, yeah, it was the ultimate musical test, if you like.

James Tocchio: I want to ask you about some specific songs. Tell me a bit about the song called Sold Out. It is so optimistic and sort of full of life.

Richard Jacques: Sold Out is a play on words of one of my favorite bands and favorite albums, which is a cross between Selling England by the Pound and Seconds Out, which are both Genesis albums. That's why it has a bit of a prog rock feel to it.

Richard Jacques: I suppose that was a bit of my personal tribute to Genesis, which is a band I've followed since I was a kid, and I remember discovering their music. I was probably around 11 or 12 years old. I was having a piano lesson, and in the next door room my piano teacher's son was a drummer, and he was playing along to a Genesis song called Turn It On Again, which is a great song from the eighties, I guess, and it had this very strange time signature. I think it's in 13 8 time signature, which is very unusual. So you have this kind of regular beat, and then it sort of skips at the end of each measure, and then the same again, and I was fascinated listening to this, and I was trying to do my piano lesson, but I had no interest at all. I was just really interested in this music, and that's where I discovered Genesis. And then I went back to some of their earlier catalogue from the early seventies when they formed, and their keyboard player, Tony Banks is such a genius of harmony and chords. Their chord changes when they go from a verse to a chorus or into a new section, just has this huge lift, and that was something I was consciously trying to do with that track. I wasn't trying to copy Genesis or thinking I'm as good as that band who, I think, are amazing, but I just really appreciate what they did for me as a young musician and as a fan of their music. So it was a conscious decision to try and at least give a tip of the hat to them. If you see what I mean.

James Tocchio: Yeah, that song. There's just something about the way it's flowing, and feeling great, and then it just changes. It shifts, which is perfect for a racing game, because it's like a downshift and we start accelerating or surging forward. It's just so perfect. Do you remember Long, Long Road? I feel like you were having a little fun with that one.

Richard Jacques: I mean, I was having some gentle fun. I certainly wasn't trying to be disrespectful, because I like that kind of music, and it does give me a smile, and I do think there's a certain element of humor that the country artists put in when they're doing a song like that, and because it's a racing game, I didn't want it to be too serious.

Richard Jacques: But yeah, of course, I wanted to try and capture the flavor of what genres are all about and what their foundations are. But yeah, with Long, Long Road I tried to tell this quite amusing tale and I had a bit of fun with it as well.

James Tocchio: And then Let's Get It On Tonight has a totally different flavor.

Richard Jacques: It was around that time when Will Smith was pretty big both over here and in the US, so I would call it hip hop, yes, but it's got more of a party vibe to it, and I've always liked that kind of stuff. I tried to do it in a way that I thought if I was creating that song, if I was that artist, that's the invented artist on the radio, and I would have been sampling a 1970s record, and then add some hip hop loop, drum loops, and stuff over the top. What would that sound like? So then I had to try and create a hook from a seventies record and then build on top of it. So I kind of had to deconstruct it and build it ground up.

James Tocchio: I think what is most impressive to me about this soundtrack is the versatility that's on display, and just how effective each song is at capturing a mood and a vibe. Even the main menu music is really interesting. You could describe that particular song as simple, but I'm sure it's deceptively simple.

Richard Jacques: I think that's probably the last one I wrote, because I don't know whether it was a decision about whether we needed menu music, how long the menus are going to last, and I thought, “Well, I'll write a track.” And I just wanted that energy when you fired up the console, right from the beginning to have that energy. It's a hard house track I suppose, and it's got the my original TV 303 bass line doing all the squelchy sounds. It's quite a simple hook, but it works. It pushes things forward, and that's what I was trying to do with those rhythms that I was playing around with in that track.

James Tocchio: Can you talk a little bit about the vocalists that you use? I know that TJ Davis is featured in many of the songs, but I know there's other vocalists as well.

Richard Jacques: Yeah.

James Tocchio: What was like to reunite with with TJ Davis after you worked together on Sonic.

Richard Jacques: There were quite a few vocalists, maybe six or seven. I’d previously worked with TJ on Sonic R, which was released in 1997. So when this project came up, I wanted to get her involved, and knowing that she is also a very versatile singer. I knew that she's got a great rock voice, and she's got a great pop voice as well. I'd already made a little mark by my list of tracks, saying which would be good for her. Got in touch, and she was very keen to come back.

At that time she was in a record contract with a record label, so we weren't allowed to use her name, so she went under the name of Helena Davidson. And she did maybe five or six songs. Some of the dance stuff, one of the jazz funk tracks and a couple of the rock tracks she did, and some of the pop stuff as well, because she's very good at changing her voice to suit the style. So when she's singing the pop stuff, she has a very kind of younger, more whispery voice, and then she can really belt out the rock numbers as well, because she's got a very strong, powerful voice. And then, yeah, some of the other singers. Stephen Stapp was a UK singer who did, I think, two tracks.

And then we had MC Momo, as he's known, doing the raps. And Gavin Skeggs, who did the Disco. Everyone was picked for their vocal sound and style, coupled with the tracks I was writing to make sure the fit was working.

James Tocchio: What was the most challenging style for you to compose?

Richard Jacques: I think for me some of the rock stuff for one of the San Francisco radio stations, because it doesn't come naturally to me, and I had to work extra hard to make sure it was on point, both musically and lyrically. Apart from that, the others were fairly straightforward, and I was pretty comfortable on all the others.

James Tocchio: What was the most fun radio station to compose for?

Richard Jacques: Oh, that is a tough question, I would say West Central 1, which is a sort of pop station based on a couple of radio stations in London, because you would have an all female sort of vocal pop group, and then you would have, you know, something a bit more on the Brit pop edge, and then you'd have some, maybe something a bit dancey or a bit disco. And that was a lot of fun because I grew up listening to all that kind of stuff. And it's a very commercial radio station. Yeah, they don't play anything too edgy. But it it was quite fun trying to just get a bit more out of it, taking those tracks a little bit further than maybe they would in real life.

James Tocchio: When was the last time you listened to this soundtrack?

Richard Jacques: There's a Youtuber, a young lady, and she played the whole thing and reacted to every song, and I listened. It was interesting, seeing her reaction, and I think she might be a musician because she was talking about some of the jazz stuff and some of the brass. But that was nice, just seeing someone literally react in real time to what they were hearing, and I was prepared for some very honest reactions, shall we say? But it was good to hear it again. Some of the jazz stuff I really enjoy. I was unpacking some old archive boxes. And I found the original sheet music. So I'm going to make sure that's all scanned and digitized.

James Tocchio: This soundtrack doesn't have an official release, correct?

Richard Jacques: That's something I'm sure I could do myself with Sega's approval. I'm sure they would be open to it. It would be nice to have a physical, maybe a low run vinyl or CD release, and maybe to get it on streaming services. I'm sure a small number of vinyls or CDs would be suitable. It'd be interesting to see if people are interested. I do read a lot of comments, and you know that it would be nice to get it out there. I'd love to remix some of the tracks and just bring them up to date a little bit. There's a few things where I can hear the odd imperfection, and if I was allowed to do that, then I would definitely re-release it.

James Tocchio: What’s the feeling when you see that people are still really loving the things you’ve created 20 or 25 years after you made them?

Richard Jacques: Yeah, it is amazing. And it's something I never ever expected. As far as I'm concerned, I was just doing the best job I could to make the best music I could for the game I was working on at the time, and I try not to think about reviews or press or the games reception, because I've got no control over that.

What I find very humbling is there's a whole new generation of fans for this soundtrack and some of my other soundtracks that weren’t yet born when I was writing them, so for them to be a fan of the music, and then, they might find an emulator, or an old Dreamcast, or Saturn console to play the game, to join the dots and see what the experience is like, is great. And if they find the music alone is a very pleasurable experience. It blows my mind, and I'm grateful to people for listening. It always puts a smile on my face.

James Tocchio: That's perfect.

Life is short, I want to be happy, and other reasons to love Virtual Boy.

There are several valid reasons why Virtual Boy failed commercially. It was expensive. People don’t like having things attached to their faces. The words “Virtual Boy” sound weird when we say them out loud in the same way that reading or speaking the word “orange” over and over eventually looks and sounds alien and dumb.

Orange. Orange.

Orange. Orange. Orange.

There are several valid reasons why Virtual Boy failed commercially. It was expensive. People don’t like having things attached to their faces. The words “Virtual Boy” sound weird when we say them too much, in the same way that speaking the word “orange” over and over eventually makes it sound alien and dumb.

Orange. Orange.

Orange. Orange. Orange.

And, of course, there’s the headaches.

Old timey reviews of Virtual Boy, and the many dozens of subsequent retrospectives from today’s YouTubers, which certainly harvest those early reviews to a great extent because who, besides me, really owns a Virtual Boy, all exclaim(ed) loudly and annoyingly that Virtual Boy was and remains a machine designed primarily for the purpose of making headaches.

Virtual Boy entered my life in 1995 when I was eleven years old. A longtime Nintendo Power subscriber, I compulsively feasted on the magazine’s Virtual Boy preview issue for months, until Christmas morning finally delivered the beautiful red future to my gaping retinal maw. I played it endlessly then, and still do for a few hours every month, and in thirty years of use, it has never induced a single headache. Furthermore, my eye doctor assures me that it played no role in the rapid deterioration of my eyesight, which shifted from perfect 20/20 vision in 1994 to near blindness beyond six feet in 1996.

What conclusion may we draw from such diametrically opposed experiences? Only one; that the supposed headache havers are boring liars, weak of eye and brain.

More to the point, Virtual Boy has enough excellent games to make owning and playing one worth any quantity of mythological headaches.

Red Alarm is one of the most beautiful electronic anythings I’ve ever experienced. This wire frame, low-FPS, proto-3D flight rail shooter is Star Fox for people who know how to read. When I played it in 1995 I thought “This is what the inside of a computer looks like. I’m living in the future.” And when I play it now I think, sadly, “No one will ever make anything this interesting again.”

Wario’s best 2D platformer appears on the system. Virtual Boy WarioLand is fast, punchy, hilarious and challenging, with a 3D depth mechanic that was incredible in its day and remains inspired today. It has phenomenal boss battles and a soundtrack by the legendary Kazumi Totaka. There’s literally nothing to detract from the game except that people found it easy to whine about the color red.

Jack Bros. is a remarkably well-crafted 3D dungeon crawler by the people who make Persona, and the first Megami Tensei game to release outside of Japan. People who direct games at Atlus still talk about it today (when I make them), and if you bought the game new in 1995 you could sell it tomorrow for a profit of $1,550.00. In this economy?

Mario Tennis is simply great. Teleroboxer is a cyberpunk Punch-Out!!. V-Tetris is 32-bit Tetris Effect and has the eighth-best and second-classiest box art that’s ever been printed for a video game.

All of these games are dope as hell.

I don’t know how else to say it, nor how to convince you. Indeed, I don’t know how to convince anyone it seems, because whenever I pitch an article to magazines about how the Virtual Boy is ackshually good, editors lose my number. But it is. It’s actually good.

It’s called flight.

I get it. It’s easier to sit upon a stack of established opinions and poo poo the silly things. It’s fun to laugh at Virtual Boy’s off-putting name and repeat for the thousandth time the dead-wrong factoid that Gunpei Yokoi, the visionary designer who made Nintendo billions of dollars with his Game Boy, was fired after the failure of his Virtual Boy (I debunked this myth myself in an interview with Gail Tilden, former Vice President of Brand Management at Nintendo). It’s easy to whine about headaches and scoff at a library of games totaling just 22 (of which just 14 came to the USA).

But to do so is self-limiting and predictable and dull.

You know what’s better than that? Liking weird shit. Being a weird shit enjoyer.

Take Panic’s Playdate, for example. Now there’s a modern-day Virtual Boy if ever there was one (complimentary). It’s a cloyingly cute yellow square with a delightful, anodized aluminum hand crank, a catalog of built-in and downloadable games from young devs like Diego Garcia (Casual Birder) plus astonishing gems from established legends such as Katamari Damacy’s Keita Takahashi (Crankin’s Time Travel Adventure). [FYI, Keita Takahashi told me he made this game just to see if he could make something super difficult - what he called a “From Software” game.]

Photo by the author. Don’t look at it. It’s mine.

The Playdate too is a monochrome, offbeat, mostly ignored machine. Like the Virtual Boy, I love it and play it more than I do my Switch.

By the way, are you mad that the Switch 2 only comes in charcoal grey? Because you should be. What happened to weird tech? The Walkman Bean, colorful translucent iMacs, and the Sony Sound Burger? And remember third party controllers for the Nintendo 64 which had a turbo switch and a screen-printed graphic on one of the three(!) handles that radically shouted Maximum Impact!?

Holy shit. All of that was cool as hell. Just like Virtual Boy. And if you don’t think so, I have bad news; you’re boring. If you don’t wake up your next computer’s going to be a space grey MacBook and you’re gonna die a virgin (metaphorically).

I can break it down pretty simply.

Life is short.

I want to be happy.

This is why I love Virtual Boy. ∎

Interview Transcript: Keita Takahashi, May 2025

In May 2025, I interviewed Keita Takahashi, the creator of Katamari Damacy. Some of that interview material is published in issue 274 of Retro Gamer Magazine in a feature titled “The Making of Katamari Damacy.” However, the scope and focus of our conversation was much broader than what could be used in that article. Here’s the complete transcript of my interview with Keita, where we discuss much more than Katamari.

In April 2025, I reached out to Keita Takahashi to arrange an interview, thinking Retro Gamer Magazine might be interested in publishing some sort of feature on this singularly gifted game creator. I never really expected that I’d get to chat with Takahashi, a game designer whose work I have adored for over 20 years, but remarkably, he wrote back almost immediately and we set a date. This good fortune was even more surprising when you consider that his new game, To a T, was nearing the end of its development and was due to release in just a month’s time.

I conducted the interview in May, and though I was nervous to talk with someone whose work I had loved for so long, Takahashi ended up being one of the kindest and most thoughtful creators that I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing. It was truly special for me, and I’ll be forever grateful.

The article itself took some effort to get rolling, but eventually, Retro Gamer Magazine accepted my pitch and “The Making of Katamari Damacy” was published in issue 274. That article contains a number of key moments from my conversation with Takahashi, however, due to space and scope of focus, much of the interview is not included in the magazine.

Here is the complete, barely-edited transcript of my conversation with Keita Takahashi.

Keita Takahashi: Hello!

James Tocchio: Hello!

Keita Takahashi: How are you?

James Tocchio: I’m very well! I see the Prince behind you. [The Prince from Takahashi’s first game, Katamari Damacy, sits on a shelf just over Takahashi’s shoulder.] Is this your work studio?

Keita Takahashi: I mean, it's a garage. Why I'm wearing the jacket. It's so cold.

James Tocchio: Well, I'm so thrilled to talk to you, and the editors at the magazine are so happy that you were able to find the time. So I thank you for that and thank you, as well, as a fan. I've been a fan of your work for a long time, and the things you've made have brought me a lot of joy.

Keita Takahashi: Thank you. Thank you for playing my stupid games.

James Tocchio: And thanks again for the demo access to To a T [Keita’s newest game, unreleased at the time of this interview.] We've played that a few times and love it, my two young daughters played as well.

Keita Takahashi: Oh, how old?

James Tocchio: They are 8 and 9.

Keita Takahashi: Okay.

James Tocchio: They're obsessed with it. I catch them humming the songs that the giraffe sings. And then the other day I walked upstairs from my work office, and they had drawn this little drawing of your giraffe character. [Shows Takahashi a drawing of the character Giraffe.]

Keita Takahashi: Perfect.

James Tocchio: You must be very busy right now.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, I'm sorry in advance. My brain is. My brain is still stuck in the work, so maybe it's not ready to give proper answer interviewing? But I will do my best.

James Tocchio: You're getting close to the end of the development cycle.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, I think so. Yes, at least. For the day one patch. I have to keep working on additional patch.

James Tocchio: The release date is in May.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, may 28th

James Tocchio: You're very close. So, I’m interested in chatting with you about your career and of course Katamari [Retro Gamer Magazine had commissioned me to write a feature titled “The Making of Katamari Damacy” published in Retro Gamer #274]. But I would also like to chat about To a T.

So if you don't mind, do you think we could start with the early days. What was your first job in the game industry?

Keita Takahashi: My first job was the artist, 3D artist of the Arcade Game Department in Namco.

James Tocchio: Do you remember any of the games that you worked on at that time?

Keita Takahashi: To be honest, I didn't make any product at all. I know the other people who join with me were able to ship some consumer products for the arcade, but I'm not. I was so picky about the project. Also, my boss understand what I want. So he protected me, which is super great. Instead of pushing me to a project as soon as possible. He gave me a chance to join some small project instead of the bigger one, which is a prototype project.

Since I didn't have the computer or any console when I was study sculpture at the Art University I have no idea how to make a video game, so I needed some time to learn how to make it. How the game is… how do you say, assembled or made. So I think I spent a few small prototype project, and then I think that was maybe one, no, almost two years and then all project is canceled.

James Tocchio: Oh, wow!

Keita Takahashi: But I was not the game designer. I was just a part of the artists, so it was not my fault. [laughs] Maybe. Maybe.

And then even my boss kind of feels so bad since I didn't ship any consumer product. He said ‘Hey Keita, do you want to join the other like a regular project.?’

But I couldn't decide if I want to join or not, and I just ask him. ‘Give me more time,’ and then the Katamari Damacy idea just came from… I just saw. I just came up with the idea. It was great timing. And then I had to present a pitch of the idea to my boss. And he said, ‘Oh, that may be cool.’

James Tocchio: Was this the same person that had sort of been guiding you through early days at the company?

Keita Takahashi: Yeah.

James Tocchio: That's really lucky to have someone like that.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, I mean, I was just lucky. I just keep being lucky in this. I still don't, I still don't understand. I still don't believe that I have been working on video games since the start of my career. It's almost 20 years. It's crazy.

James Tocchio: And did you know that Katamari Damacy is in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City?

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, yeah, I know.

James Tocchio: Were you involved in that? Did they talk to you, or did you go there.

Keita Takahashi: I didn't go there, but the Moma asked Namco, when I was in the Namco studio. It's crazy.

James Tocchio: Do you look at that with pride, or is that something you don't think about?

Keita Takahashi: Mmm. I mean. It's hard to describe. I have two [thoughts on this]. Maybe the one is that I don't care. Another one is that yeah, just ignoring. Yeah.

James Tocchio: I understand. I've spoken with a lot of people who create things, and many of them are simply focused on the thing that they're creating. And they're not too worried about all of the extraneous aspects that surround it. They're just focused on the work. Does that sound like how you see yourself?

Keita Takahashi: Maybe I mean, I don't know what's the difference between art and video game. I still don't know what the definition of the video game is, as well. So if they just pick the Katamari as art, that's fine. But I don't care about the genre or categories, it's so stupid.

James Tocchio: You just want to make what you want to make, and if it resonates with people, then that's great.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, if the people makes happy or smile with the game I made. That's, that's it.

James Tocchio: Are you a musician? Besides game development. [Takahashi is shaking his head incredulously. And smirking.] No, you don't play any instruments. I’m surprised because your games have such amazing music.

Keita Takahashi: Because I have amazing composer around me.

James Tocchio: Who composed the music, for To a T.

Keita Takahashi: My wife, Asuka [Sakai].

James Tocchio: That's wonderful. It's great music. My girls have been humming it for days. Do you play video games? Besides the ones that you're working on.

Keita Takahashi: No, no.

James Tocchio: It’s funny. I've talked to a lot of people that develop video games at a high level and many of them don't play video games.

Keita Takahashi: Oh, really.

James Tocchio: They're too busy making them, I think. They're just so focused on their work.

Keita Takahashi: I think so. But even when I was not busy I don't play video games.

James Tocchio: But surely you played games at some point.

Keita Takahashi: Yes. Of course. Yes. But in the art school, I think I stopped playing the video game because I realized that making something is more fun than just playing.

James Tocchio: Do you remember the first game that you ever played?

Keita Takahashi: Oh, the first one, I think that's a Japanese specific console. I forgot the name. It's a Cassette Vision. Maybe it's before the Famicom. No, yeah. Before the Famicom. I had a friend who had a lot of video game console. And it was called a Cassette Vision. Do you know that? Let me check, let me search.

James Tocchio: I'll have to look it up.

Keita Takahashi: It looks like an Atari.

James Tocchio: Okay.

Keita Takahashi: Oh! This! [Keita shows me the Cassette Vision.]

James Tocchio: Oh, Cassette Vision. I don’t know that one.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, this is a Japanese.

James Tocchio: 1984. That was when I was born, you know.

Keita Takahashi: Oh, really. Oh, Super Cassette Vision, maybe this Super version was my 1st game. It was super simple.

James Tocchio: 1984, yeah, I would imagine. So let's talk a little bit about Namco and those early days again. When you pitched Katamari, was it difficult to get them to give you a team and funding, and all of that?

Keita Takahashi: So that, my boss, said that's gonna be difficult to use the regular path to get the green light. So he was working at the different department to teach students how to make a 3D model as an artist. The curriculum was making the game with them. So my boss was very smart. He picked my idea as a prototype game.

James Tocchio: I see.

Keita Takahashi: And then we hired some engineer who were almost fired from the company because, I don't know, I forgot the reason, but the other department want rid of them and we rescued the person, then used them as an engineer in the prototype project. So [the team was] the student, the artist, then an almost fired engineer, and then me as a very beginner, amateur, a no experience game designer. Then I think we had at least two professionals.

James Tocchio: To guide the ragtag group.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, then I forgot how much time we spend to make a prototype but six months or five months. And we use the Nintendo [Game]Cube hardware, because I believe, for the engineer that was easier than PlayStation.

We made a prototype, then pitch to the company. The initial goal was to exhibit the game to some event. I forgot the name. But there's an art event. Then we put the game as a school project.

James Tocchio: I see.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, then we show the game to the executive in the company. Also the other employees as well. It seems like they like the game a lot. So then my boss came again, then negotiate to the executives, but they said, I guess they could not spend a lot of money for such a new experimental game. So they wanted to use outsourcing company, not the Namco itself. But I really wanted to work inside of Namco team because they are more higher spec. But you know, it was better than nothing. So I just. I said, Okay, let me go to the outsourcing company. Namco is at the Yokohama, around Tokyo, and the outsourcing company was more West Side, in Osaka. So I moved to Osaka.

James Tocchio: What about when the sequel was made? Was Namco more more willing to spend some money on it after you'd proven a success.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, I think so. But the reason I wanted to make Katamari was there's so many similar games, like even now there are so many similar games, but that’s 20 years ago.

Namco was making very same similar types of games, like a racing game, a shooting game, RPG, it's nothing new. They made a more unique game in 1980s or ‘90s. So I wanted to make a very unique game that only play, in the game like a… you can just drive a car, if you have a car, there's no point to play racing game, because you have a car right. You can play football. You don't need to play football game, right?

So I wanted to make a video game that only a video game can do. So making the sequel is not what I wanted, so the first time they asked me, I refused. But it seemed like they still wanted to make a sequel, even without me. Which also I hated.

So I decided, maybe just only one sequel. And then I leave after this. So yeah. I did it.

James Tocchio: Yeah. So you made the sequel with them, and then you became independent. You wanted to go see what else you could do, you're always looking for the next interesting thing, not just repeating what you've done.

Keita Takahashi: I think so. Yeah.

James Tocchio: Are you happy with how things have gone since then, with all the different projects that you've done?

Keita Takahashi: Of course not. I mean, I think that all developers are never happy about their games.

James Tocchio: I find that with many people who create things. I talk to a lot of writers as well. And we're just never happy. You finish something, and even if it's a success, it’s embarrassing. You don't want to look at it. You don't want to think about it. You want to just move on to the next thing and do better next time. So I think I understand.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah.

James Tocchio: You said you weren't content to be a 3D artist. You wanted to create a game of your own. That said, your background was 3D art and making models. When you were making Katamari, did you spend any time yourself creating character models in that game, or the models and objects? Or were you directing artists to do that kind of work.

Keita Takahashi: I did. Actually, I made The Prince model by myself. also, animation. I mean, I like to. I like modeling. I like the making picture. Of course I was. I like art.

But this was a video game company. That's a very huge chance to make a video game. So that's why I just set my goal. If I join the company, I should make my own game rather than just being the artist, because this is a video game company, not the artist company.

James Tocchio: I understand.

Keita Takahashi: That's it. [Takahashi shrugs.] Then I made it. Oh, that was so lucky.

James Tocchio: I find it very interesting how understated you are. You've created one of the best video games of all time, and you talk about it like, well, it's not a very big deal.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah. But I mean, it's hard to tell. It’s just a video game. Right?

James Tocchio: Yeah. Okay. I see where you're coming from. [I don’t.]

Well there’s a reason that I asked you about making character or object models. And that’s because some of the models in Katamari, for me personally, and I know other people have spoken about this before and written about this, and a lot of fans say this- it's almost as if every single 3D model in that game is special. There's something about them. Taken as individual components, they're all gorgeous. They're beautiful, they're charming. They're cute. They're funny. There's just some magic about each and every little object that you can roll up in that game. And so obviously, a lot of care and attention must have gone into that. So I was curious if you were sitting there for hours and days and weeks creating all these little creatures and objects and people and animals, or if you were more directing, saying, no, this cat needs to be cuter, or this mouse needs to not have legs and just roll around. So I was curious about the nuts and bolts of creating these games, I guess.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah. I think that all came from the spec of the PS2. Also the concept of the katamari, because we need to put tons of objects on the katamari ball. My understanding was the GPU was not so strong in the PS2, but we want to show a lot of objects as much as possible. So each single object would need to be very simple, low poly. and then, if they’re low poly then I know this is some decision for the art style, but for me, if it's low poly, then the texture shouldn't be very realistic. The texture also should be simple. Easy to understand.

James Tocchio: Right, yeah.

Keita Takahashi: I don't think it required a lot of time to get that direction of the art. I spoke to the art director, and he also agreed to that direction. I know many people love that simpleness and clean texture like. What… Minecraft.

James Tocchio: Yes. I think your designs are a little more charming than Minecraft. But I know what you're saying. Okay, let me ask specifically about one model. I think it was in the sequel? Your scuba diving cat? Do you remember the scuba diving cat [In the Katamari Damacy sequel We Love Katamari, there’s a stage which takes place mostly underwater and this stage contains a number of fun little low poly cats wearing low poly scuba masks and snorkels].

Keita Takahashi: Yes.

James Tocchio: Have you seen that the low poly scuba cat has been tattooed on people, and people are making it into T-shirts and all sorts of pins and key chains.

Keita Takahashi: What?! Really? No, no, no. I didn't know that.

James Tocchio: There's a lot of internet threads and memes and posts on social media of the snorkeling cat, where people are sharing their tattoos and their shirts and drawings.

Keita Takahashi: Oh, that's crazy!

James Tocchio: I wonder if you knew who created that particular model.

Keita Takahashi: I don’t remember.

James Tocchio: Yeah, that's hard to remember.

Keita Takahashi: I mean, we only had two level designer, including me. So either me or the other one made that.

James Tocchio: But that art style has followed you along in your career, though you say that it was originally brought about by technical limitations. But as technology has improved, you've maintained that similar sort of aesthetic. I know that simple design is actually extremely complicated. It's more difficult to design something simple than it is something super complex.

But do you think that sort of that aesthetic is a part of your identity now as a creator? Or is that just what you're drawn to you.

Keita Takahashi: Oh, I think I just like the simple design. I don't know, because of…. It's hard to tell why I like the simple style, or why I choose this style. I think I don't have any confidence about my drawing skill. I'm not good at realistic photo type of art, but I do like the manga, or just simply drawing like a picture book, or young children drawings. Maybe that's why.

James Tocchio: If you weren't a game designer, do you think you would be an artist making children's books, or something else?

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, the art school. So there was a in Japan, maybe only in Japan, that the Japan is very unique. I'm not sure, because I was not able to spend my time in other country. But it's not only Japan, I mean for me, the college time was four years. I thought this would be the last freedom for me before I go to the company.

James Tocchio: The real world.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah. So I have one big concern, which is. I like, make something I like. I also like drawing something. But then I'm in the sculpture department, which is very unnecessary stuff. So I had no idea how to earn the money after graduate to school. And also, yeah, I was not clear what I want to do. I had this idea from way before I went to the art school. But I choose that because I like the art. I like making something. I spent four years to think about what I can do, what I want to be, what I want to make.

And the answer is super simple and stupid. But since I got the idea by myself, so that is very big to me. It's not something I steal from others, and it’s still precious and still stick to me even after graduate school, after like 20 or 30 years, which is make people smile. That was a very unforgettable moment. At the school I made a goat shaped flower pot, planter.

Yeah, you know this story.

James Tocchio: I've seen a picture of your goat. Yeah.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, goat.

James Tocchio: I think I saw it on Twitter. I think you posted it. But tell me the story again.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, yeah, yes.

So, every time in the arts college, you need to do like a presentation like a show and tell about stuff you made. So I did. I made a goat shaped flower pot or… planter. And for my presentation I just put the water on the water can, and then adding the water on the back of the goat, and the extra water [drained through] from the… how do you say this… boobs.

James Tocchio: The udder??

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, udder [laughing], but that stupid presentation makes the student or other professor laugh and smile. That was a, that was a moment for me. I think, “Oh, this is what I want to do! This is much nicer than like ‘Oh, this is beautiful and nice.’”

James Tocchio: Then is it fair to say your whole career has been an attempt to make people smile.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, I think so. Also the other stuff. Other important stuff was I wanted to make a tool rather than art, because I saw the other students just throw away the stuff they made after the presentation, which I really hated. So if I make a tool, then I can keep using this, and I like that idea as well. So that's why I made a goat flower pot and other stuff, I made a low table that could be transformed to a robot.

James Tocchio: Oh, wow!

Keita Takahashi: I still have that in my house.

James Tocchio: Do you have the goat planter?

Keita Takahashi: No.

James Tocchio: Where did the goat go.

Keita Takahashi: Broken.

James Tocchio: Aw, well that does happen sometimes.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah. So making a tool and making people smile was my two biggest make a point, but the making people smile is more higher priority for me. So I don't know, if I was not being the game designer, maybe I could be a comedian or something [laughing].

Right: Keita, speaking to me from his garage studio.

Left: Me in my office, star-struck.

James Tocchio: Is your ultimate hope for To a T that it just makes people smile then?

Keita Takahashi: I think so. Yeah, that's it. I think I was cursed about the idea of interactivity. In doing the Namco, because I believe the interactivity is most highest priority, for the video game, because of the interaction is the key of the video games.

James Tocchio: Right.

Keita Takahashi: I don't know any other media that has interaction other than video games. So that's why I was making like a Katamari and Noby Noby; Katamari is rolling, Noby Noby is stretching and Wattam is connection and exploring. But after I finished Wattam I had a time to think about the video games, and I just noticed, “Oh, I could be happy and smile to watch the anime or manga, or just movie.” I thought, “Oh, I don't need any interaction. Just consuming something can make me smile. Which is nice.” And I thought, “Oh, why, I got the curse from the interactivity.”

Also, I still didn't know what's the definition of the video game. I know there's so many genre or category inside of the video games. But there's no specific definition of what a video game is, because we don't need lose or win. But the video game is not only about the collection or fighting, or how do you say, solve the puzzle. Timing, press the timing in like a sound game music game, but there could be more. So I just this time for To a T I tried to ignore interactivity. I didn't put interactivity to the first priority.

I said, “More narrative and more like an unclear atmosphere.” How do you say, like a nice… nice vibe? Or mood?

James Tocchio: Vibe, okay. Yeah. Nice vibe.

Keita Takahashi: I know that I'm very unclear and abstract, but that's what I want to try to put into the game, because the current situation, the real world, our world is so… [mischievous smile] so nice, you know.

James Tocchio: Yeah, gotcha.

Keita Takahashi: So I wanted to make something very positive. Put the spotlight to our life, not a billionaire’s life.

James Tocchio: The story of To a T seems like it's going to focus on the main character’s struggles with being picked on for something that makes them different from other people. Now, I haven't played the whole game, so I don't know if that's where we're going with this, but that's what it seems like to me so far. Were you picked on as a kid in school.

Keita Takahashi: Yeah, yeah.

James Tocchio: Did that influence this game?

Keita Takahashi: Of course, that's a part of the reason I picked the student time or school time for the main scenario. Yeah. I was bullied between elementary and middle school. But somehow, I survived through that tough time very nicely, which is also another lucky [thing] for me, and I learned a lot of stuff from that hard time. So, at this moment, when I look back at the past, that was a nice experience for me, but I know when I was younger that was very tough.

Maybe the reason I was bullied was I was fat, very fat. So, if there's a t-posed stuck person in your class… Different from people. Same thing.